LAUREN ALEXANDER

25/04/2017 12:51

Michelle Janssen:

So I decided to only ask female’s for an interview, because I am a female

so it is much more interesting for me.

Lauren Alexander:

Yeah and there are also not that many females in our department.

are female.

Yeah it is strange, right? I also

find it very strange. I notice it

a lot. I am the class coach of the third-year students. I have to be the boss of the evaluations, so

I have to be the boss of all the

man and it is really tough some-

times. You would think because

so many of the students are female, it would be re-flected in the teaching staff, but it is not the case, I am actually the only female teacher in the third year at KABK.

a moment of conflict?

Roosje was teaching with us

for a while in Playlab class, but

not anymore. Conflict no, not really. To be honest I think they are grateful because none of them wants to do this job. It is a lot of administration and many things that take a lot of extra time. But I also really enjoy it. It gives you a view into students lives. You get

a little bit more of a personal connection with them.

was one of the reasons to start teaching and to become the head of the department together with Niels. So she could show that it can be possible for a woman to be on top, and you can do graphic design, and you can have children, and you can do fun things, you can do everything. Is this also a motivation for you to teach or are you just pure focused

on I want to spread my vision on all students, or maybe this is something you did not think about?

I do totally connect with that and I also do feel that pressure as well, especially with students who come from outside of the EU. Because I was also a non-EU student, I also mostly connect with those students. They come to me for advice, like where should we search for internships because

we want to stay in the Netherlands and we don't know how to.

It also has to do with being female, and also because I have gone through the same experience. Early next year I'll

get a Dutch Passport. I've been here for 10 years and I never got married or anything like that.

That was my struggle for many years, negotiating how to work for myself as a freelancer and stay in the country. It was really hell for a certain period. I feel like those students from outside the EU definitely connect with me and I feel responsible for them. I'm happy that I'm there because otherwise there would be no one for them to really connect with about this particular issue. I do see as well that as a female I give the girls in the class someone to look up to. I feel, maybe it is sub-

conscious, that some people connect with me more or less

than with for example Niels, who

I often teach with, and it definitely has to do with the male-female dynamic. I don't know if I would really put myself in the position

as head of the department, at least

not yet.

But I do see Ghalia teaching in the Middle East and how that is really important because there are only females in her class. Who are all wearing headscarves. The girls really grow up during their studies and sometimes lose their head-scarf by the fourth year. I think

for her it is also really important that she is there. The girls really look up to her.

What is your view on this?

Yeah in the next couple of years

I will face this question more and more since this year I am turning 34. Although I don’t really know yet, I would like to have children

I think, it would be a great ex-

perience, but I don’t know how I would manage it. Right now my living situation is quite compli-

cated and I need to travel a lot.

I moved to the Netherlands in 2006, eleven years ago and I feel quite settled in Amsterdam. At

the same time, I am currently in Dublin a lot. I am staying here now because my boyfriend lives there. And I also work sometimes the Middle East and often travel there. I have been working in the United States quite a bit, especially during the summer times. Not really your ideal situation to start a family. Sometimes things are confusing and really depend on the assignment which we are working on. I am always free-

lancing so to say. My stable jobs are the KABK and next year when I start teaching at the Sandberg.

The rest of the time I am moving around. I do have a studio in Amsterdam where I have been working since 2012. I actually work there together with Bart

de Baets. But let’s say I am not a studio designer like I don’t take interns anymore because I am

just not there that much. That is just how things are right now when it comes to children it could be doable, but I would probably need to adapt. I have a lot of artist friends who are very sceptical towards having children because they think having children ruins your career, but I don’t agree.

I always felt like I would really want children. And you could say that children can be very portable. But

I completely understand that you would think that having children ruins your life. I mean parents always say that children could give you so much. But there are also a lot of sacrifices you have to make for them.

How old are you?

22 so I am not thinking abouthaving children anytime soon, no.

Something I was wondering, and

I feel it is kind of related to what you said, as a KABK student I feel, and

I notice it more and more so I become more aware of the fact that

I am shaped by this school. For example, teachers are giving you certain resources. They talk about certain topics in a certain way. They talk about things in a very out-spoken and opinionated way. All these things I feel are shaping me and of course, I am picking what I want and what I agree and disagree but if everyone in you surrounding is saying this is

good and this is bad, this is black and this is white, etc. It gets kind of hard to disagree. How do you deal with this responsibility?

Hmm, that is a good question.

I do a lot of projects in the third year with Niels Schrader. We combine my subject, interactive media, and his, Design. The two

of us have quite a specific dynamic together.

‘specific dynamic’?

In collaborations, you have diff-

erent roles and you have different strengths and weaknesses in relation to the other person you are working with. Niels has quite

a strong vision as to the projects that we could do and the collaborations that we could connect with. He is really good

at connecting with external partners outside of the school. That is an example of what I would say is not really my strong point. But within the project

itself, we have developed and separated tasks.

Depending on the project, I focus more on storytelling, content and context and he focuses more on design details and production.

In a way, the tasks are divided between the run-up to the project and the development of the project.

There is a crossover for sure but sometimes it's nice to, especially in teaching, separate a little bit what your feedback will be because otherwise students

can get confused, but we are constantly experimenting with

our format.

I don’t know if you have teachers that currently do things together?

Ok yeah, that makes sense, practically speaking. But I guess the projects we do in the third year are quite different from the assign-ments in the first year. It is more focused on your personal statement about your work. We are now doing a collaboration with the book museum in The Hague called Museum Meer-

manno.We selected six books

that have something to do with political ideas. Books are like Spinoza, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, famous voices from history from around the 1700’s. The students need to research these books and formulate their own statement related to contemporary issues. With that, they are making an exhibition in June.

The projects that Niels and I are doing are really about formulating your own opinion about things. I often fear that our opinion about things, as you say, could dominate how a student should approach a project. Especially in the third year when we have exchange students and sometimes they don’t even really know where they are or even where the next class is.

We are trying to push students to derive design from content, rather than from the form. In general, I think this ability to do drive design from content is what KABK is trying to achieve.

a media (form).

Sometimes I worry that there is not enough time for the craft of Graphic Design. We spend so much time on the concept, to

keep on sharpening it. I do believe there is value in very basic edit-

orial content training, through a lot of different iterations or to work with text and images. Sometimes it feels that there is not enough time for the basics. There are a lot of students, there are still 45 students in the third year, so to see everyone on one day is im-

possible sometimes. Usually per semester we only do one or two big assignments...but in term

of dominating the minds of students…

I guess in the end, what I like about the KABK is that there are

a lot of different teachers. Even though the teachers are often in more or less in one line, they

have different voices. I have ex-

perienced in other educational programmes, in other schools

that it can become quite pro-

blematic when there are too few teachers. For a lot of students

who change to KABK, if they come from Willem de Kooning

for example, their classes are only really with two teachers. At least KABK does provide more variety

in the kind of influences students are getting.

I think I definitely learnt a lot from the other teachers. As a teacher, you don’t know what you are doing in the beginning and you also don’t really know what you have to offer. You can imagine if you suddenly have to stand in front of a class for 3,5 hours to deliver information to students, you need quite a bit of confidence in what you have to offer people.

I think that teaching, in general, is an issue of confidence, in what you have to offer but also to be yourself as much as you can and not to be ashamed of that.

In generally I have learnt a lot about different styles of teaching and how to handle many types of students. It would be a totally different story if there were half

as many students. I have taught

in other places where there were

only ten students, and that is a completely different dynamic. Handling volume at KABK is quite something.

We have managed to do some amazing projects with the stu-

dents, like crazy collaboration projects, we did a big exhibition

at the Ministry of Finance now twice. So I learnt how to do that

as well, how to manage a lot of individuals and how to make one outcome in the end. For sure I have learnt a lot from being and teaching at KABK. Niels is a fantastic teacher, I have learnt

a lot from him.

Of course I did a tiny bit of research on you and the things I found in your work seem quite political, critical. Like focused on political aspects, especially in the Middle East.

How did you get there that you are focusing on political topics so much? Why do you think things like that

are important to talk about?

Well I wasn’t always focusing these issues in particular, but yes the most recent projects the direction you describe. Basically, I studied together with Ghalia, who I still collaborate with. We studied together at the Sandberg between 2006 and 2008 and then after our studies in 2009 we started working together. I did my master study at Sandberg about images in Dutch media representing Africa as a general concept. At that time, which is quite funny to notice,

you used to see quite a lot of NGO (Non-governmental organisation) advertising of poor black people. These huge posters on Leidseplein and everywhere. Everybody who was asking for money outside the Albert Heijn was asking for money for starving people. But you don’t see it anymore, I don’t know why that it.

much of that kind of things.

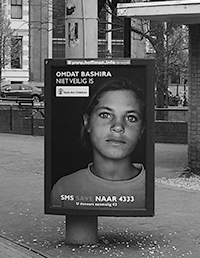

Maybe this variety of advertising has shifted to social media. For example, I now see an image of a refugee girl when I walk out of

the train station in The Hague,

now that you know, you will probably notice too. A beautiful refugee nine-year-old girl with bright blue eyes.  Because I came from South Africa to the Netherlands I found that very interesting. In South Africa,

Because I came from South Africa to the Netherlands I found that very interesting. In South Africa,

you don’t see images like this portrayed in the media.

Because it is a different context, even though NGO’s also exist there, you don’t have that style

of marketing. A human being is a reason to donate to an NGO and I see this very much as a Western European phenomenon.

I developed a whole project around that and I was, for example, interviewing all the people who created these adver-

tisements. I asked them why they made the images like that, and how they made them. Really looking into the politics of

how an image was made and distributed, why that certain image was chosen, etc. This was my topic of research. Researching images from a Western per-

spective, which was strange

to me because I saw it from a different perspective.

Ghalia was also working on similar projects. She is a refugee herself and came to the Nether-

lands many years ago and settled here. She was developing a project about mapping detention camps in the Netherlands. Which were quite hidden from the Dutch publics’ view at that time and it was quite difficult to get to them. She was photographing them

from the outside and sort of investigating where they are and mapping them out.

We both had

a similar interest in that kind of journalistic way of working and trying to incorporate that in our design interests. Both of us worked in advertising previously and in commercial design contexts and I think we just connected in our work ethic and interests. We both really wanted

to create projects, or a space for ourselves: to create projects that we really wanted to make. Just from a research and investigative point of view. And that’s that, the rest was history, we just continued like that.

I consider it more or less a miracle actually that we continued work-

ing together. I am sure you know what it is like to work with other people in your class. Sometimes it works and it is good and other times it is really horrible. One person does all the work and another person doesn’t do any-

thing, you know how group dynamics work. For us, it is literally the same now as it was then. The only difference is now that she lives in Egypt, and it is now a long distance relationship.

In a sense, we also became more involved the art world. We all of

a sudden became participants in bigger expositions and big com-

petitions. However, in a way, we are doing it in exactly the same way as previously. Just following our nose, doing investigations

and travelling around, finding things and making projects

from our findings.

People often ask how do you make money with this variety of work? It is a priority for us, not to rely financially on the work we are doing as Foundland. It does make money but we are not dependent only on Foundland for work. There is Foundland, which is

more or less like a lifestyle.

And then there is teaching and freelance work, which we earn money from.

that you do, teaching, Foundland

and freelancing as well?

Yeah.

What is it like to work in theart world? I am really interested in what you

said about the Western NGO’s way

of marketing. My parents had a

‘foster parent child’ before I was

born, her name was Naba. That is

the reason why my second name is Naba because this girl was kind of their first child. Even though they only supported her financially so she could go to school and could buy books and stuff like that. And in return, she would write letters back

to my parents but they never saw her. Later it turned out that a lot of the children that were supposed to get the money that the organisation got from their donators, were lost. So I will never know for sure if this girl actually excited. All of it could have been fake. But for the rest of my life,

I am connected to an African, maybe fake, child in my name.

That is horrible.

But it is also quite funny that every time I write my full name somewhere everyone is “oh Naba, where does it come from.” “Oh yeah, it is African.” “Oh cool, how did you get this name?” And then I have to explain this weird story.For me, it was quite a revelation

to consider charity, not as the generosity of North-West Europeans but to realise that it is an industry. It was interesting to interview people who make images and what you discover in the end is that they need to make a campaign and are obliged to make specific, pre-determined imagery. So they send people

over with instructions and a list

of images that they have to

go and collect. So one time a female smiling, one time a poor male looking helpless. A pre-scripted list of imagery before

they even arrive in Africa.

What really motivates and inspires you in your work? I want to know

for your teaching job, but also for Foundland and your freelance work.

Well I guess with teaching a motivation would be that you

get to take part in a student's development. Especially at KABK, it is like 45 developments. There are so many students and there is so little time. So to be part of their own development and to guide their thinking and I think maybe to open doors that they had never thought of before. This is a great motivation, to see improvement and development. Perhaps that is

a really cliché answer.

And then with Foundland work

I am really driven by the possi-

bilities that the content of the projects can open up. It is totally an obsession. For example, we had an exhibition opening last Friday. It was an extension of an older project that we did. We asked refugees who live in Europe and

in the United States to draw a basic floor plan of their home in Syria. It actually turned out that for everyone it was a very valuable experience. If I ask you to draw the family house where you grew up you actually know every corner in your house.

not really, but yeah I understand.

Oh well, probably it is a challenge for you to pick which one would feel closest too. Which one is actually home? That is kind of a crazy question but maybe it is a combination between all of them. Anyway, the exercise of drawing a place that you are never going to return to, from memory. You would also never return to your old homes I guess but at the

same time…

Yeah it is a different kind of loss and you realise how people had

to use their house in times of conflict. They couldn’t, for ex-

ample, heat up all of the rooms

so they would only gather in

some rooms. If there was bomb-

ing going on, they had to gather

in rooms with strong walls. So the house kind of becomes this place of shelter rather than this is a nice room or a beautiful view or what-

ever. The project was quite simple and really interesting and it was amazing what it allowed people

to remember.

I spent the last couple of weeks interviewing one guy. He is now living in Amsterdam and I know him quite well, I did three inter-

views with him. I asked him on the first day ‘Can you think about your home and can you draw it very roughly.’ He drew a very rough version of the floor plan and told stories about all the things that happened there. It

was really fucking crazy, really horrible shit happened there that. He told me that it was the first time he told anybody about the stories. It was really a traumatising few hours.

The next interview, he drew his house really precisely he wanted

to show his son when he got older. The next and last time we met we scripted what he was going to tell me about the house. So it became more like a scripted interview that we worked on together. Then we used that scripted interview in the exhibition. This is an example of the kind of content that I am working with. It has something to do with sociology, anthropology, with art and drawing, imagery, etc. I just really like doing what I do. So yes it is an obsession. That is my motivation, obsession.

But that is probably also the nice thing about it.

Yeah definitely, Maher is an awesome guy and I can see what it is providing him and he wants to do it. Of course, every project is different. For this example, we (Foundland and Maher) are working together towards some kind of show, there is going to be some kind of outcome in the end: an exhibition. Where we show all the drawings and we show the video. You know it is an exhibi-

tion about personal stories about migration, so it is a good fit.

With Foundland we, for example, get approached by people to do talks. And certainly, we do turn things down because they are simply not good. For example, there are often requests like; on behalf of all Syrian women, say something about empowerment. Obviously, Ghalia is a Syrian woman, and she could com-

ment, but we are cautious with those kinds of things. They basic-

ally just search for a woman from Syria who is kind of in the spot-

light to fulfil their own purposes.

Tell me about your book recommendations. Why and

what did you send me?

So the first one, do you know

the first one that I sent?

This is a really nice book, I think you might like it. I bought it when I was at the Sandberg. It is about Pierre Bernard who has a studio, Atelier de Création Graphique. The book, “My Work is not my Work” is a great overview of his life. He is a graphic designer and he was working with campaigns for French public space, and public institutions, like for ex-

ample the Louvre. He was working in the 60s/70s and really concern-

ed with making more humanistic campaigns as opposed to adver-

tising campaigns. I really enjoy

the graphics and it is a nice

design reference.

The other book I sent you is called “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” by Paolo Freire. It is written by a Brazilian pedagog. I got this book when I was writing my master thesis. For that particular master study, I was working together with eight South-African students and the project was called Cardboard monument. I was basically work-

ing together with them, doing research in a particular area.

There is a monument that is

quite problematic in the space.

For three months I was working together with this group of, all boy, artists and coming from quite an impoverished South-African background. The project thought me a lot about how to approach people that are coming from an oppressed position. In South Africa, you have a dominant

white and black, oppressor and oppressed dynamic, which is very present in society. Far more than in the Netherlands, I think. Even though in the Netherlands it is also there, but it is not really as

in that people need to deal with it on a daily basis.

So this is what the book is about, how to deal with the other, especially in the role of a pedagog. For me, this was life-changing also in creating a kind

of empathy for the person you are teaching, from what background and from what mind frame are they coming.

else recognises that.

Yes I think this is definitely a useful book for any teacher to read. What Freire particularly covers, and I what I found quite interesting, is that he talks about the concept of assumed laziness.

I think it is identifiable in all cultures: A rich white Dutch person might say; “Those lazy Turkish people who don’t want to work”. Especially in South Africa you see this a lot. “They are so lazy, they can’t do anything, they just can’t help themselves”: it is the attitude of the oppressor. What the idea of laziness actually is and what that means and what kind of perspective this comes from might make you question what in fact laziness is? The position of the oppressed comes from a deep insecurity and lack of entitlement and may be perceived as laziness. Which ok for the students at KABK is not really that relevant but I think it is good, especially

if you have exchange students, who come from totally different perspectives.

ground in a way that I never realised that I was so much shaped by certain cultural things. But now, I live with foreigners, I study with foreigners, I have more Swiss people in my daily life that Dutch people. Now I realise how extremely Dutch I am. Like bikes?

Well, totally yes. Bikes. No, but also an international culture at

the KABK for example. People came here to study, they didn’t go somewhere else. There also loads of things that are really special I think. In general, I find Dutch people very honest. You definitely don’t find that everywhere trust me. Like from the States or also in the Middle East you find yourself being flat out lied to all the time. That would actually never happen in the Netherlands. I think for Dutch people they don’t see the logic in it. You might as well confront yourself with the truth and go forth, you know.

There are definitely good aspects that you should probably remind people of too. Don’t be afraid to do that. It is probably anyway lame to talk about identity as being restricted to any nationality. Because we are all so mixed and we are all a bit of everything, you know. Even you have a bit of African in you.

the rest, I am not really sure.

You can never ever escape from that. (laughing)

Yes sure, but I also have a bit of Western sell-out in me too. Exactly.Yeah probably, I hope I am still there and you are still there.

Yeah I definitely hope that too.I wish I could have this conver-

sation with students I currently have. But there is no time, space

to do that. It is also a bit tricky because you have a more intimate relation with them. I hear stories about how they guess what my life is about. And I am like, I am right here you can just ask me if you want to. I feel like I know the students much better than they know me. They present them-

selves constantly to me through their work and I just respond to them. My assumption is that

they get to know me, through my responses but actually that is not really the case.

I just want to know.

True. We also have some teachers in the third year who don’t have any work online and who don’t really introduce themselves with their work. But the students at one point are like: “hey you have to show your work”. Teachers then find this very confronting it feels like they are being judged for what they do and not for what they teach. Because these people have been teaching for years and years and years. They find that really intimidating and students don’t really realise that.

I also think there is also value in having been teaching for that long and it definitely should not be discarded. At the KABK especially there is this huge emphasis on the teacher being a famous superstar. Which is totally crazy because in other places it is not like that at all. At KABK were are just teachers for one day a week and in other academies, teachers work for like 5 days of the week and it is so difficult for them to do also other stuff on the side.

matically mean you are also a good design teacher. So there is definitely value in that. But it is also really cool if your teacher does something

really cool.